Chickens: The 'Impractical' Effort To Save Our Most Important Companions

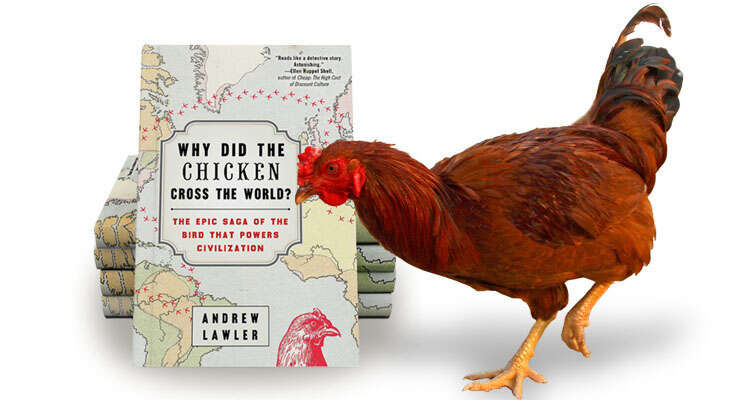

Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization by Andrew Lawler, Atria Books 2014.

The chicken as "world conqueror"

The June 2012 issue of Smithsonian magazine published an article celebrating global chicken production and consumption. "How the Chicken Conquered the World" features a cartoon of the "Chicken Conqueror" dressed as Napoleon. Eager to glitz the story of chickens as "crispy" corpses and world conquerors, the editors thought it would be cute to dress up the account with "astounding" images. Readers were invited to chuckle with the editors: "What if you were to take portraits of raw chickens, dressed up as some of the most famous leaders in history . . . Chickens-Dressed-Like-Napoleon-Einstein-and-Other-Historical-Figures?"

Other than the Napoleon cartoon, the chickens dressed as "historical figures" for the article are naked, headless corpses. The article's coauthor is science writer Andrew Lawler, whose book Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? looks at why the chicken, of all animal species on earth, emerged, in his view, as "our most important animal companion."

According to the book jacket, Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? presents "the sweeping history that this humble fowl deserves." Lawler entertains the reader with vivid accounts of how chickens have been exploited through the ages for medicine, sacrifice, sport, science, food and war, right up to where, through his eyes, you can watch a contemporary cockfighting spectacle in Manila, witness a Kaporos chicken-swinging ritual in Brooklyn, peek inside a chicken research laboratory at Michigan State University, and catch a glimpse of an industrial "broiler" chicken shed where these very world conquerors – our "partners" in the project of powering the human race with their proteins – sit in dead silence until the chicken catchers, pumped up for violence, come cursing, kicking, clacking and hollering at them, a squad of terrorists descending on birds who are sick and lame and never harmed anyone.

Lawler's summary of cockfighting fits nearly every scene he shows: "The contest is about the human rather than the animal. . . . [T]he bird is simply an extension of its owner." Research for his book brought him to United Poultry Concerns on the Eastern Shore of Virginia – part of the Delmarva Peninsula including Maryland and Delaware where more than half a billion chickens are confined in thousands of toxic sheds throughout the region, and millions are slaughtered each week – to interview me and see our sanctuary chickens in October 2013.

He says he was initially leery because I responded to his request for a visit by saying that his Smithsonian article was despicable and that he needed "a whole different perspective, spirit, and attitude toward chickens"; thus his surprise when instead of a lecture he was invited outdoors to meet our chickens, of whom he writes that "After the numbing uniformity inside the Delaware broiler shed, the individuality of each of Davis's birds is startling and unnerving."

Lawler says we agree that the effort of United Poultry Concerns on behalf of chickens is "impractical, ineffectual, and wildly anthropomorphic." This may be his interpretation of my saying, on pages 227-228: "I think chickens are in hell and they are not going to get out. They are already in hell and there are just going to be more of them. As long as people want billions of eggs and millions of pounds of flesh, how can all these animal products be delivered to the millions? There will be crowding and cruelty – it is just built into the situation. You can't get away from it. And we are ingesting their misery."

Yes, so I said, but pessimism about an atrocity and its outcome is not the same as feeling, or being, "ineffectual" in one's commitment to alleviating the atrocity, nor is it an assessment or equivalent of one's (or one's organization's) ability or accomplishment confronting the atrocity. The fact that a situation may be beyond one's control does not make one's actions toward it, per se, "ineffectual." Lawler's book, and maybe his conscience, benefitted from my book Prisoned Chickens, Poisoned Eggs: An Inside Look at the Modern Poultry Industry, and from other writings of mine that he read. He told me during his visit that until he encountered the idea in Prisoned Chickens, Poisoned Eggs that by eating chickens we are eating their misery, it never occurred to him. And probably most readers never thought of it either, but perhaps now they will.

I believe his book benefitted also from our personal interview and as a result of his seeing our sanctuary chickens living and being treated in ways that differ starkly from how chickens look, act, and are treated in the various situations our species forces them into – situations that, as Lawler describes cockfighting, are about "the human," not chickens. The chickens, poor souls, are simply extensions of their owners, whether it's cockfighting, religious sacrifice, genetic manipulation, or whatever. Those of us who want chickens to live sanely as chickens, instead of as what Lawler calls a sanctuary's "fowl flotsam" and "misfit poultry" – we are not the anthropomorphic ones. The abusers are.

Anthropomorphism originally referred to the attribution of human characteristics to a deity. It now refers almost entirely to the attribution of consciousness, emotions, and other mental states, once commonly regarded as exclusively or predominantly human, to nonhuman animals. Anthropomorphism based on empathy and careful observation is a valid approach to understanding other species. After all, we can only see the world "through their eyes" by looking through our own. The imposition of humanized traits and behaviors on other animals for purely selfish purposes, forcing them to behave in ways that are pathologic to the animals themselves, is not the same thing as drawing inferences about the emotions, interests, and desires of animals rooted in our common evolutionary heritage.

The "humble chicken" as Napoleonic conqueror . . . To a thoughtless person, dressing up a defenseless and defeated creature as a "conqueror," representing chickens as our companions in our destructive ventures toward them, may seem clever and cute; otherwise, it is callous and cruel – and far from new. Anthropomorphic derision of other animals in a spirit of malevolent jollity is an age-old ritual in the carnivalesque tradition of taunting and tormenting helpless victims, both literally and figuratively. Opposing the sanctimony of pious sentiments and ceremonies, the carnivalesque spirit emphasizes mockery, sarcasm, cruelty, gluttony, and pleasure in the abuse of bodies. In the carnivalesque tradition, humans and other animals are mixed derisively together. Only the eyes, wrote cultural analyst Mikhail Bakhtin, "have no part in these comic images," because eyes "express an individual, so to speak."

Apart from the Napoleon cartoon, all of the chickens depicted as conquerors in Lawler's Smithsonian article, of which Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? is the fruition, are headless. Looking at them, I thought of former Tyson chicken slaughterhouse worker Virgil Butler, writing before he died, in 2006, of how the chickens who were about to be killed would stare at him with their eyes as they hung upside down on the conveyer belts, fully conscious and filled with excruciating electric shocks administered to their faces through cold, salted, electrified water: "They try to hide their head from you by sticking it under the wing of the chicken next to them on the slaughter line. . . . You can tell by them looking at you, they're scared to death."

Virgil Butler became a vegetarian when he could no longer look at a piece of a dead chicken or any other meat anymore without seeing "the sad, tortured face that was attached to it sometime in the past." Lawler is not a vegetarian or vegan-friendly. Despite the wealth of delicious animal-free foods that can be found even in the rural area where I live, he dismisses them, whether in ignorance or by design, as mostly unworthy items that merely "mimic the bland taste of industrial chicken." Instead, he feeds the fantasy that "More humane genetics, treatment, and living conditions could roll back the worst abuses against our companion species without unduly interfering with the flow of cheap animal protein to our cities."

Cognitive science shows that chickens are birds with "a deep intelligence," who "see the world in far greater depth and detail than we do," have "a sophisticated method of communication," and "a complex nervous system designed to form a multitude of memories and make complex decisions." However, a researcher at Michigan State University who does the usual hideous things to hens that people like her have been doing for decades says that chickens "are not kind and gentle. They peck at each other and pull feathers out" and don't always use the "freedom" of their crowded confinement systems "wisely."

This slap at chickens is an example of false anthropomorphism. Chickens do not pick and pull at each other, or get into "cockfights," in their tropical forest homes. They are foragers with a strong family life whose picking at one another in captive squalor and sterility is a form of distorted behavior engendered by living conditions that frustrate their nature and reflect the psychopathy of their captors. Thirty years of keeping chickens, and I know. Sure they have spats now and then – so what? They're sentient, social beings, not robots. When Andrew Lawler visited our place, I took him upstairs to look down at the chickens in the yard, surrounded by trees and moving about in the loveliest rhythms and patterns of their daily activities.

Lawler calls the modern, "engineered" pure white debilitated chicken, "a poster child for all that is sad and nightmarish about our industrial agriculture." His account of how chickens got this way is one of No Exit. He travels to tropical forests and mountain tops in Asia, where the families of red jungle fowl – ancestors and contemporary relatives of domesticated chickens – live shy of humans, but they cannot escape. They and their forest habitat are disappearing, and the locals catch them and use them as live bait to lure others into captivity. A village farmhand explains that the "smart and secretive [jungle fowl] can swiftly die if caged by rushing the bars and breaking its neck." No matter. A campaign is underway to appropriate the genetic traits of remnant populations of jungle fowl in their shrinking forests. Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? concludes with a North Carolina ecologist – a retired employee in a nuclear weapons laboratory – thanking "our most steadfast and versatile companion," in Lawler's words, for giving itself to us. He is interested in saving the "pure stuff."