Rhino Birth Raises Questions About Zoo Euthanasia Programs

By Sophia Nicolov and Andy Flack, University of Bristol, for the Animal History Museum On Jan. 25, Denmark's Copenhagen Zoo, announced the birth of a southern white rhinoceros calf. For the zoo, the birth of a calf of this subspecies for the first time in thirty-five years is hugely significant for reasons related to its own self interests. It marks the zoo out as "successful" and generally leads to greater visitor numbers.

Beyond that however, for zoos which have increasingly shifted focus from simply warehousing animals to playing an active role in species preservation - and perhaps for the public at large - they are emblems of something more profound. The calf born at Copenhagen Zoo last week represents a result for conservation programs, as well as translating the idealism of conservation into practical reality. But the practical reality of zoo-based conservation programs can sometimes be unpalatable. Last year, the Copenhagen Zoo provoked global outrage when it euthanized a number of its healthy animals supposedly to improve the genetic health of the species in captivity.

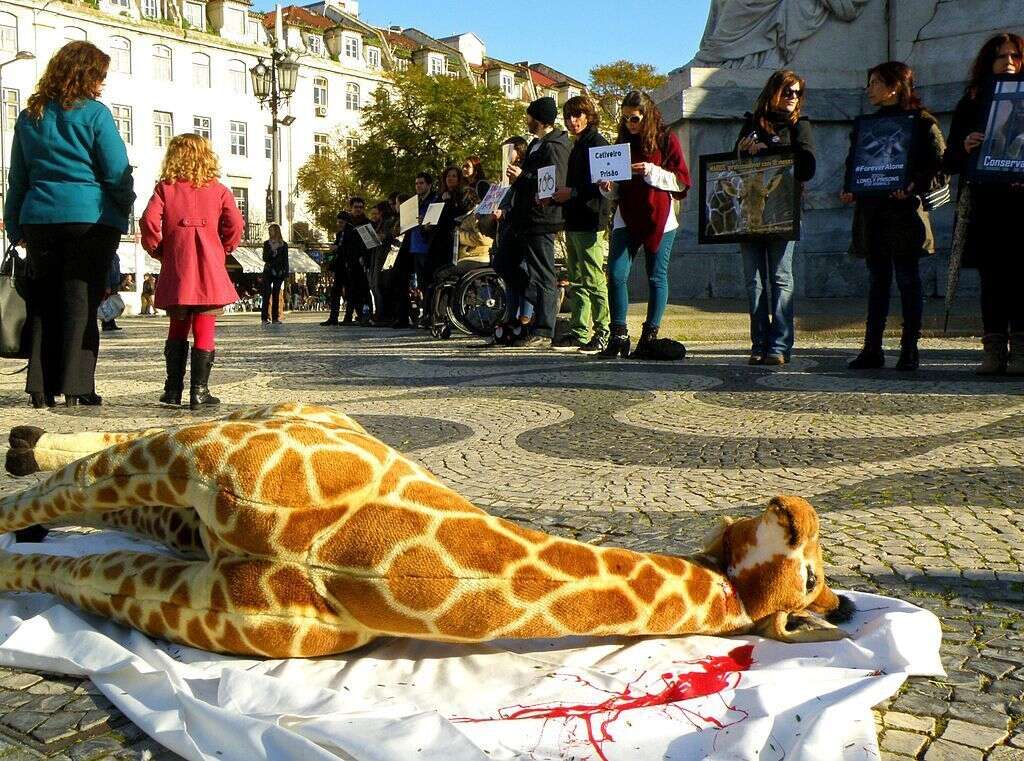

In February 2014, the zoo controversially euthanized a healthy male giraffe, reasoning that this was to prevent inbreeding with other captive giraffes. Just one month later, the zoo once again decided to kill four healthy lions of the same family, including two 10-month old cubs, to make way for a new male as part of a different breeding program. This is all the more perplexing considering international recognition of Copenhagen Zoo's work with lions and, more importantly, the perpetuation of this policy despite the emergence of significant global objections to the practice more widely. All this raises important questions about the nature of individual animals' value and just how much the birth of a single creature in captivity can actually affect wild populations and wild places. This makes the birth of the Copenhagen Zoo's latest southern white rhino much more complicated than it first appears.

The southern white rhino is an important example of the waxing and waning fortunes of wild creatures. Not only were its numbers driven to the brink, but its survival is considered one of the greatest conservation success stories of the twentieth century. At the end of the nineteenth century the population had been so reduced by trophy hunting at the height of imperial activity in Africa it was believed the creature was on the verge of extinction. In 1895, a pocket of around 100 were discovered in the Umfolozi-Hluhluwe region of South Africa. The region was then set aside as a protected area and, with close management throughout the 20th century, the population rose to around 20,000 individuals. While population growth has slowed since 2010, South Africa's environment minister Edna Molewa revealed Jan. 22 that in 2014 the population had declined for the first time in a century.

The report also revealed that a total of 1,215 southern white rhinos became victims of poaching last year, with 827 alone slaughtered in the Kruger National Park. These figures become all the more worrying when we consider that only 13 were killed in 2007. As we know, this astonishing decline is being driven by the ever-growing demand for rhino horn in parts of Asia for pseudo-medical and recreational purposes.

The coincidental timing of the release of this data and the birth of a calf in Copenhagen is especially significant in rendering the calf a symbol for the species as a whole. The birth provides hope for the successful conservation of the species after a year of devastating losses. Just last month, Melbourne's Werribee Open Range Zoo welcomed a southern white rhino, commenting that it was a milestone for worldwide conservation efforts. Due to the popularity of baby animals, despite the controversies surrounding zoos, there is the potential that this calf, like others, will become a focus of public awareness about the fragility of animal life as well as mobilizing support for conservation efforts.

For those with an eye on the plight of endangered species, the birth of an animal represents a species moving, if only momentarily, away from the brink. It shows that species loss and conservation are not just about facts and figures but about the physical lives of individual animals. Each birth has the potential to make an impact not only on the numbers of creatures surviving worldwide, but also on our awareness of the threats facing wildlife. The survival of species is totally dependent on each and every animal.

Like so many other species, the southern white rhino faces a staggering array of threats to both its body and habitat. Despite this, global conservation programs and large numbers of people more widely refuse to give up on the possibility of saving species under threat. The southern white rhino epitomizes this mentality. There are both internal and external forces working together alongside continued government funded anti-poaching initiatives in the face of what appears to be the accelerating depletion of wild populations.

The birth of animals of a threatened or endangered species highlights just how important an individual animal really can be. Not only are their bodies a part of the physical mass of species, but their ability to influence ideas about conservation, and the way they can encourage us to make connections between our own lives and the wild places makes them absolutely critical if we are to stop species disappearing. And yet, the indeterminate value of individual animals, as Copenhagen Zoo so clearly demonstrates, means that, for the animal, the practical reality of life in a breeding program has the potential to be little different from the precarious life of animals in the wild.