Do Animals Commit Suicide?

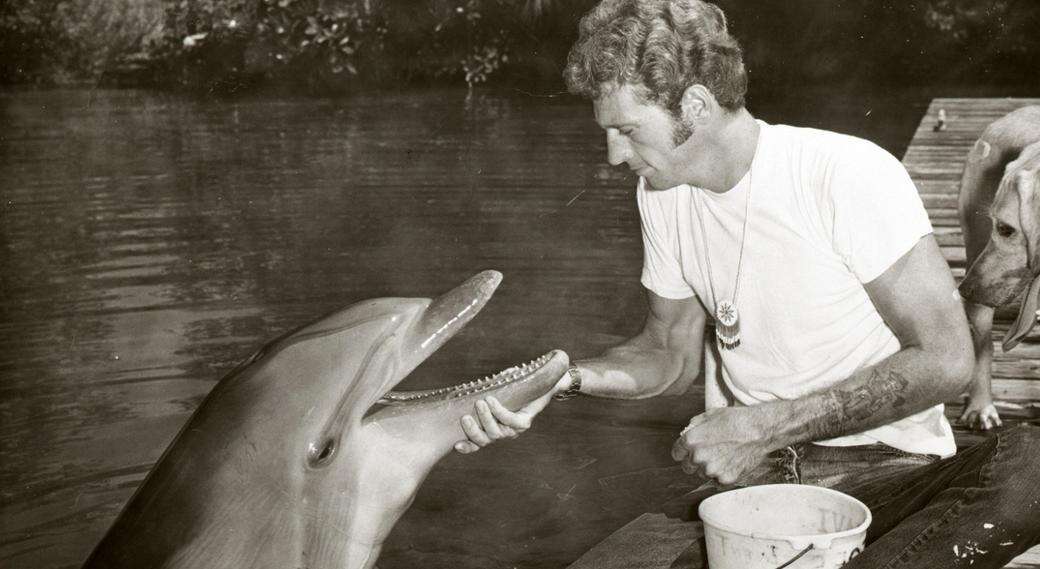

Decades ago, Ric O'Barry, founder of the Dolphin Project and central catalyst of the documentary "The Cove," trained a dolphin named Kathy.

Ric O'Barry with Kathy.The Dolphin Project

Kathy was one of the cetaceans who portrayed the popular television dolphin "Flipper" in the 1960s. Over the show's duration, O'Barry had come to form a close connection with Kathy. He lived with her and the other animal actors for 7 years, O'Barry said in an interview with PBS. "I lived with them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and we bonded ... [I was] very close with them." Which is why what Kathy did in front of O'Barry years later changed the trajectory of his life from trainer to activist forever.

"Dolphins are not automatic air breathers like us," O'Barry told The Dodo. "Every breath is a conscious effort. That means they can end their life anytime by simply not taking the next breath."

Ric O'Barry with Kathy.The Dolphin Project

"I got a phone call from the [Miami] Seaquarium [where Kathy had been living after the show ended] telling me she was not doing well," O'Barry told PBS. "I had already left. The show was over."

O'Barry went to check on Kathy in her tank and saw she was covered in blisters. "She was black from sunburn because she spent most of her time on the surface of the water," he continued. "Her fin was bent. That's nature saying there's something wrong here."

And then Kathy swam right over to him. "She swam over and looked me right in the eye, took a breath, and just held it. Just held it," he told PBS. "So I grabbed her ... and she sank to the bottom of the tank. I let her go and she sank. I jumped in and pulled her to the surface."

In O'Barry's arms, he says, Kathy had committed suicide.

He's since seen dolphins behave like Kathy time and time again - dolphins commit suicide with frequency at the controversial annual Taiji dolphin slaughter in Japan, which was depicted in the documentary, "The Cove," according to O'Barry. "I've been witnessing this same scene for the last 13 years - multiple times a year," he told The Dodo.

Dying dolphin in Taiji JapanThe Dolphin Project

"Most recently, in early September during a capture a dolphin broke through two barrier nets and swam right up to my feet, looked me straight in the eye, thrashed around on the rocks while holding her breath and died," O'Barry says. "The hunters got her off of the rocks and she sank to the bottom, dead."

But it's not just dolphins who commit suicide, say some researchers.

Captive bear in bear bile farm in China.Animals Asia

Captive bear in bear bile farm in China.Animals Asia

"Recently, Chinese media has reported that a captive bear on a Chinese bear farm killed her son and then herself after she heard him cry out in pain," wrote Marc Bekoff, former professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, in Psychology Today.

The mother bear reportedly broke free of her cage after hearing her cub's cry, "causing [bear] 'farmers' to run away in fear. She then ran to the cub's side and immediately smothered [him]," writes Bekoff.

Then, the mother cub ran headlong into a wall and killed herself instantly.

Doubts have repeatedly surfaced about the veracity of this tale but it - and O'Barry's experience - raises an important question:

Can animals actually commit suicide?

The story of the lemmings

Animal suicide is rarely discussed without mentioning an oft-referenced story about lemmings, small rodents found in the tundras of North America and northern Europe.

LemmingShutterstock

Following an explosion in population every few years, "masses of lemmings were seen to travel down from their mountain homes to the coast," wrote Edmund Ramsen and Duncan Wilson in a recent study about animal suicide. Undeterred by the sea, "they swam out until they drowned, littering the beaches with their corpses. When marching, they did not seem to move aside for any obstacle, as if, one writer described, they were 'impelled by some strange power.'"

The behavior of lemmings has been of interest to scientists since travelers first took notice in the 19th century. Over time, all kinds of reasons for their extraordinary behavior were tossed around - from stress to population control. In fact, their doomsday habits were eventually featured in a science fiction book called "The Marching Morons."

Illustration of lemmings jumping to their deathsShutterstock

Ultimately, the general consensus concluded lemmings are not committing suicide. But the pendulum between the certainty of O'Barry's experience with Kathy and the uncertainty of lemmings' behavior shows how massive this difference of opinion can be.

Suicide in science

The Center for Disease Control defines suicide as "when people direct violence at themselves with the intent to end their lives, and they die as a result of their actions."

While it's well-known that animals experience mental illness, research hasn't affirmatively said animals commit suicide (or even how a human-centric definition like the CDC's might apply to the animal kingdom). There have, however, been some scientific explorations into the topic.

Ramsen and Wilson's recent study about animal suicide, referenced above in the account of potentially suicidal lemmings, expounds on the centerpoint of this whole debate: whether or not animals who commit suicide are able to know - or anticipate - their impending death. Even more specifically, can animals find a method to "accomplish it?"

In the study, Ramsen and Wilson refer to French sociologist Emile Durkheim (who wrote an essay called "Suicide" in 1897). Durkheim analyzed whether dogs purposely starved themselves to death after their masters died and, if so, was that considered suicide? Durkheim's own analysis led him to believe it was not. "It is because the sadness into which they are thrown has automatically caused lack of hunger; death has resulted, but without having been foreseen," he wrote.

In essence, even if it's unknown if animals do commit suicide, it is a worthy debate, because it could upset the very notion that humans are superior to animals when it comes to cognition, insight, foresight and the will to end their own lives.

Maybe it doesn't matter after all

Bernard Rollin, a leading scholar on animal welfare, ethics and rights issues, says he doesn't believe animals commit suicide.

"You can certainly look at the lemmings and maybe some other similar cases and say they don't meet the definition of suicide," Rollin told The Dodo. "Because it isn't a thought-out attempt to end your own life."

Rollin says his opinion is based on the unlikely fact that animals understand the concept of the future. "I've written papers on euthanasia," he says. "With human beings, death not only stops your current experiences, but human cognition is very futurally directed. You want to see your kids graduate from college, or you want to visit Ireland. To have that you have to have a linguistic ability to transcend the present."

Now, Rollin says, some may think he is denying animals consciousness with his theory, but he would likely disagree. "I'm one of the people who first argued for their consciousness," he says. "Still, you don't do any favors by attributing overly sophisticated awareness to animals."

What about anecdotes describing family dogs who, say, leave their home and go into the woods to die? Rollin maintains that animals can be fearful of pain or distress, but he does not think dogs know they are going to die. "So, if there is no way for an animal to possibly know that everything is going to stop," he says, "how could it choose [suicide]?"

Looking at the issue from a different angle is Stacy Lopresti-Goodman, a professor of psychology at Marymount University, who does not think it is a far-fetched notion that animals might be so severely depressed as to lose their will to live.

Lopresti-Goodman conducts research on chimpanzees currently living in sanctuaries to understand how confinement, social isolation, maternal separation and physical abuse in previous settings (like laboratories) have affected their psychological well-being.

Poco, a chimpanzee living at Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary in Kenya, was kept in a cage for nearly a decade before being rescued. He now meets the criteria for PTSD, according to Lopresti-Goodman.Lopresti-Goodman

"If we think back to Jane Goodall's seminal observations of chimpanzees in [the Gombe Stream Research Center in Tanzania], a small chimpanzee named Flint became socially withdrawn, stopped eating and showed signs of depression after the loss of his mother, Flo. Shortly thereafter, he died," she says.

"I'm not saying he committed suicide," she says, "but if Flint was a human who was so severely depressed at the loss of a beloved family member that he stopped eating and subsequently died, this would be considered an example of someone willfully starving themselves to death, which meets the definition of suicide."

Lopresti-Goodman says in her own research she has witnessed severe, self-inflicted injuries by animals, including biting off fingers, deeply scratching into their own flesh or slamming their head against the ground. "Again, if we saw humans engaging in this self-destructive behavior, we would certainly be worried and infer they may be having suicidal thoughts," she says.

What it boils down to, according to Lopresti-Goodman, is that science isn't always willing to accept that human emotions and ways of thinking exist in other species as well.

But evolution and common sense, she says, tell us otherwise.

"We know to a certainty that some animals feel profound sadness and grief, as well as joy," Barbara J. King, professor of anthropology at the College of William and Mary and author of "How Animals Grieve," told The Dodo.

"Some intriguing reports," King says, "raise questions about a tipping point between stress animals feel and possible acts of self-harm or suicide. It is true, though, that the issue of intent is very tricky in determining a conscious will for death."

Regardless, King says she's not sure how important it is to know whether or not animals kill themselves in the first place. "It is honestly less important to know whether or not animals commit suicide than it is to know that, when we humans harm animals in contexts ranging from the slaughterhouse to circuses and some zoos, from theme parks to biomedical laboratories, we cause terrible suffering, as we do when we destroy wild habitats."

Mainly, King says, "we need to work much harder to stop animal suffering."

Especially, she adds, since we are the cause of much of it.